Lately, there has been considerable discussion surrounding Al-Hariri’s Maqamat. A few friends of mine expressed interest in learning more about the subject. In responding to their queries, I found myself delving into the material anew, revisiting sources and rediscovering long-forgotten details.

As a result, I’ve compiled and organised the information once again—and am sharing it here with all of you.

Table of Contents

Al-Hariri and His Era — Historical and Literary Context

Abu Muhammad al-Qasim ibn Ali al-Hariri, commonly known as al-Hariri of Basra, was born in 1054 CE in the city of Basra, in southern Iraq, under the Abbasid Caliphate. This period, often described as the twilight of the Islamic Golden Age, was marked by both cultural brilliance and political fragmentation. While the central authority of the Abbasid Caliphate was waning, intellectual and artistic life continued to thrive in major cities like Baghdad, Basra, and Cairo.

Al-Hariri grew up in a prosperous Arab merchant family and received an excellent education, particularly in the Arabic language, jurisprudence (fiqh), grammar, and literature. Although not a professional writer in the modern sense—he worked in government administration and was respected as a scholar—his literary pursuits elevated him to great renown, especially through his magnum opus, Maqamat al-Hariri.

The 11th century was a time when Arabic prose and poetry flourished in new and experimental forms. Literary salons and scholarly circles were vibrant. The maqama genre, a unique fusion of rhymed prose (saj‘), poetry, satire, and storytelling, was already gaining popularity due to the pioneering work of Badi’ al-Zaman al-Hamadhani. Al-Hariri would later perfect this form and surpass his predecessors in linguistic precision and literary elegance.

The cultural atmosphere of Basra during al-Hariri’s lifetime was one of dialogue, scholarly rivalry, and religious diversity. While theological and philosophical debates were commonplace, so too were gatherings devoted to grammar, rhetoric, and philology. Al-Hariri, through his knowledge of classical Arabic and his flair for clever expression, distinguished himself among his peers.

His writing reflects not just linguistic mastery but also a deep awareness of the political and social concerns of his time. He was acutely aware of the moral and ethical decline in public life, the hypocrisy of certain scholars, and the struggles of the common man. In many ways, Maqamat al-Hariri serves as a satirical mirror to his society—cleverly veiled behind the adventures of a wandering trickster.

In short, al-Hariri’s life and works must be understood within the broader framework of the Abbasid cultural renaissance. He inherited a rich literary tradition and, through innovation, helped shape its future. His Maqamat not only stood out in its own time but has endured for nearly a millennium, admired by readers and scholars alike for its wit, style, and wisdom.

The Structure and Form of the Maqamat

The Maqamat al-Hariri is a work that masterfully blends narrative and rhetoric, form and function, wit and wisdom. Comprising fifty episodes or maqamat, each follows a consistent pattern: a narrator recounts a tale in which a central character, the trickster and eloquent rogue Abu Zayd al-Saruji, plays the lead role. Through his verbal dexterity and cunning, Abu Zayd navigates a world full of scholars, merchants, beggars, and rulers—always managing to both deceive and enlighten those he encounters.

What sets the Maqamat apart from other literary texts is its highly stylised form. The prose is written in saj‘, a type of rhymed, rhythmic prose common in Arabic oratory. Interwoven within the text are lines of classical poetry that enrich the aesthetic texture of the narrative. This hybrid of prose and verse, ornamented with wordplay, puns, allusions, and rhetorical devices, requires an exceptional command of the Arabic language—both from the author and the reader.

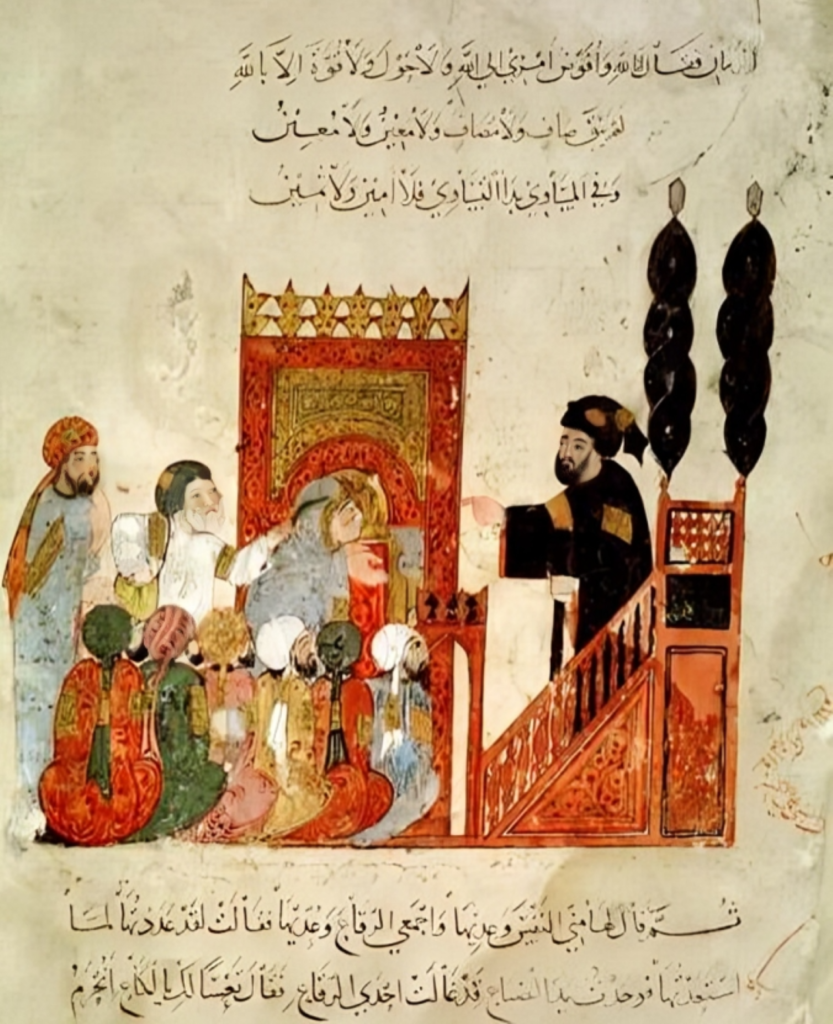

Each maqama typically begins with the narrator, al-Harith ibn Hammam, describing his travels or a particular setting. He then recounts a surprising encounter with a remarkable man—Abu Zayd—who astonishes a crowd with his eloquence, humour, or trickery. By the end of the episode, Abu Zayd’s identity is revealed, often to the dismay or amazement of the audience. In some maqamat, he reappears in new guises, sometimes as a preacher, a beggar, a lawyer, or a teacher—always exploiting social situations through language.

Despite their uniform structure, no two maqamat feel repetitive. Each episode presents a fresh setting, a new social dilemma, or a different audience—allowing al-Hariri to showcase not only his linguistic brilliance but also his grasp of human nature and society. The variety of speech registers—high and low, formal and colloquial—demonstrates the dynamic richness of Arabic and reflects the diverse voices of Abbasid life.

Importantly, the Maqamat is not merely a display of verbal fireworks. It is a text layered with moral and philosophical reflections, comic insights, and subtle satire. While readers may be entertained by Abu Zayd’s antics, they are also invited to consider deeper questions of ethics, integrity, social justice, and the power of language to both deceive and uplift.

Thus, the form of the Maqamat is not an end in itself—it is the vehicle for conveying a range of human experiences, wrapped in the cloak of linguistic artistry. Through this form, al-Hariri captures the soul of Arabic literature and gifts us a timeless treasure.

Abu Zayd al-Saruji – The Trickster with a Silver Tongue

At the heart of Maqamat al-Hariri stands the charismatic and elusive figure of Abu Zayd al-Saruji, a character as complex as he is captivating. A wanderer, a wordsmith, a trickster, and a philosopher in disguise—Abu Zayd is a master of rhetoric who survives not by the sword, but by the tongue. His name alone evokes wit, wisdom, and worldly savvy, and he is one of the most enduring characters in classical Arabic literature.

Abu Zayd hails from the town of Saruj, which lends him his epithet “al-Saruji”. Though we learn fragments about his past—his family, his learning, his hardships—he remains deliberately enigmatic. What defines him most is not where he is from, but what he says and does. He appears in various cities, always assuming a new role or disguise—sometimes as a preacher, a beggar, a poet, or a teacher—and always outwitting his audience through brilliant speech.

He is not a villain in the conventional sense, though he deceives. Nor is he a saint, though he often exposes the hypocrisy of others. Instead, Abu Zayd occupies the morally ambiguous space of the anti-hero—a figure who breaks rules, yet earns admiration for his intelligence and audacity. In this way, he resembles similar characters in world literature, such as Odysseus in Greek epics or the trickster figures of African and Indian folklore.

Through Abu Zayd, al-Hariri explores not just the art of persuasion, but the social fabric of his time. Each maqama in which Abu Zayd appears becomes a miniature theatre of society—full of false piety, corruption, vanity, and human folly. Abu Zayd’s speeches, often ornate and filled with classical allusions, are not merely performances; they are social commentaries, cloaked in humour and verbal flourish.

Despite his cunning, there is also a recurring theme of loss in Abu Zayd’s character. He often speaks of hardships, displacement, and sorrow. Behind the dazzling orations lies a man who has suffered—perhaps a symbol of the learned class struggling in a changing world where true merit is often overlooked in favour of wealth and power. This makes him not just a figure of wit, but also of pathos.

In short, Abu Zayd is the living embodiment of the maqama genre itself—fluid, clever, multifaceted, and deeply rooted in the richness of the Arabic language. Through his character, al-Hariri not only entertains but compels readers to question appearances, listen closely, and appreciate the transformative power of words.

Al-Harith ibn Hammam – The Narrator and Witness

In the literary architecture of the Maqamat al-Hariri, while Abu Zayd al-Saruji steals the spotlight with his eloquence and craft, the entire edifice rests upon the quiet, consistent voice of the narrator: al-Harith ibn Hammam. It is through al-Harith’s eyes that we encounter the ever-shifting world of the maqamat. He is not simply a storyteller, but also a listener, an interpreter, and a moral compass guiding the audience through the dazzling performances of Abu Zayd.

Al-Harith is a figure of some learning and refinement, often found travelling through cities and regions, observing the world with a thoughtful gaze. In each maqama, he recounts an incident from his journeys in which he happens upon a public gathering—a sermon, a market, a court, or a caravan—where an extraordinary orator astounds the audience. Inevitably, this figure turns out to be Abu Zayd in disguise. Al-Harith is initially taken in by the performance, but soon uncovers the identity of the trickster, sometimes with amusement, sometimes with disapproval, but always with respect for the man’s skill.

The dynamic between al-Harith and Abu Zayd forms the narrative spine of the work. Unlike Abu Zayd, who is unpredictable and flamboyant, al-Harith is consistent and observant. He is rarely the object of ridicule, nor does he attempt to outshine Abu Zayd. Rather, he serves as the voice of the reader—surprised, amused, at times sceptical, but always compelled to watch and reflect.

Al-Harith’s narration is crafted in the same ornate style as the rest of the maqamat—rich in rhymed prose (saj‘), poetic quotations, and literary flourishes. Yet his tone often balances Abu Zayd’s extravagance with subtle irony or understated admiration. He is the literary witness who documents the spectacle, giving it coherence and structure.

In some episodes, al-Harith engages Abu Zayd in dialogue, pressing him for explanations or challenging his actions. These exchanges provide moments of introspection and philosophy, elevating the maqamat beyond mere entertainment. Through al-Harith, the reader is reminded that the stories are not just about verbal acrobatics, but also about life’s complexities—about morality, survival, wit, and wisdom.

In essence, al-Harith ibn Hammam is the still water that reflects the fiery dance of Abu Zayd. Together, they form one of the most iconic literary duos in Arabic literature—one embodying linguistic genius, the other intellectual sincerity. Without al-Harith’s steady narration, the world of Maqamat al-Hariri would be a series of disjointed tales. With him, it becomes a cohesive and profound tapestry of human experience, wrapped in the splendour of language.

The Art of Saj‘ – Rhymed Prose as High Performance

Among the most striking and celebrated features of Maqamat al-Hariri is its dazzling use of saj‘, or rhymed prose. Saj‘ is no ordinary style—it is a sophisticated, rhythmic prose adorned with internal rhyme and ornate language, which bridges poetry and prose with effortless elegance. In the hands of al-Hariri, saj‘ becomes not just a medium of expression, but a performance in itself—vibrant, dramatic, and intellectually rich.

Originating in pre-Islamic oratory and Quranic revelation, saj‘ has deep roots in Arabic literary culture. But al-Hariri elevated it to new heights. In the maqamat, saj‘ is not merely decorative; it is the very soul of the narrative. Every speech, every encounter, every twist in the tale unfolds in elaborate, rhymed patterns that demand both the reader’s attentiveness and the performer’s mastery.

What makes al-Hariri’s use of saj‘ so remarkable is the precision and inventiveness he brings to it. Despite the formal constraints of rhyme and rhythm, he manages to craft vivid imagery, sharp wit, and layered meanings. His vocabulary is expansive, often drawing upon rare and archaic words, while his metaphors and allusions bring depth and texture to each maqama. The result is a text that is both linguistically challenging and aesthetically mesmerising.

Saj‘ also plays a crucial role in characterisation. Abu Zayd’s rhetorical flourishes—his sermons, laments, and boasts—are all delivered in saj‘, reinforcing his persona as a linguistic virtuoso. Meanwhile, the narrator al-Harith adopts a more restrained but still elegant style, offering a tonal counterpoint to Abu Zayd’s extravagance. The contrast between the two voices enriches the narrative, offering rhythm and variation.

Importantly, the maqamat were not just read, but recited aloud, often in public gatherings. This performative context heightened the impact of saj‘. Listeners would have marvelled at the speaker’s memory, breath control, and ability to deliver intricate rhymes with clarity and emotion. In this way, saj‘ was not only literary art—it was oral spectacle, a kind of intellectual theatre that combined language with performance.

Al-Hariri’s brilliance with saj‘ was so revered that his maqamat became models for students of Arabic grammar and rhetoric. Scholars would memorise them, copy them, and comment upon their linguistic intricacies. Even today, the maqamat remain a benchmark of classical Arabic style—a testament to the enduring power of rhymed prose when handled by a master.

Thus, in Maqamat al-Hariri, saj‘ is far more than a stylistic flourish; it is a celebration of the Arabic language in its most eloquent form. It invites us to listen as much as to read, to savour the music of words, and to appreciate the artistry that turns speech into spectacle.

Wit, Trickery, and Survival – The Ethics of Eloquence

At the heart of Maqamat al-Hariri lies a compelling tension between admiration and moral ambiguity. Abu Zayd al-Saruji, the central figure, dazzles audiences with his linguistic mastery—but often through acts of deception, disguise, and trickery. This raises a key question: is Abu Zayd a hero of intellect, or merely a charming fraudster? Is eloquence a virtue in itself, or does it require an ethical framework to be truly honourable?

Each maqama presents a variation on the same theme: Abu Zayd arrives in a city under an alias, stages a spectacular performance—be it a sermon, legal argument, or poetic improvisation—wins over the crowd, and disappears with gifts or praise, leaving the narrator and audience both astounded and bemused. He often appeals to religious or social themes, invoking piety, justice, or grief. Yet the outcome reveals the performance as a calculated act of survival or gain.

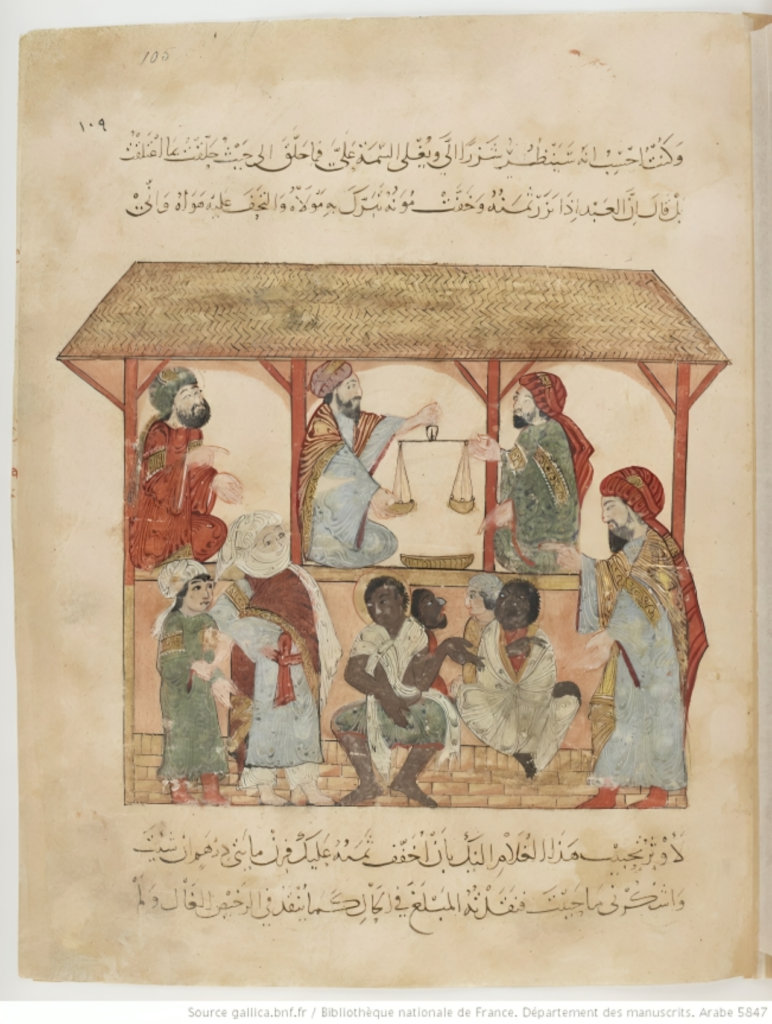

Through these episodes, al-Hariri crafts a rich commentary on the social dynamics of his time. In a world where knowledge is revered but livelihoods are precarious, where scholars may go hungry while charlatans flourish, Abu Zayd emerges as a complex figure—a survivor using the only weapon at his disposal: the power of words. He reflects the contradictions of a society where language is both sacred and susceptible to manipulation.

And yet, the maqamat do not outright condemn Abu Zayd. His intellect, education, and verbal dexterity are undeniable, and his critiques of hypocrisy, corruption, and superficiality often carry genuine insight. Through irony and humour, the maqamat subtly expose the absurdities of social and religious pretence, allowing Abu Zayd to act as both participant and satirist.

The narrator al-Harith, with his scepticism and occasional rebukes, provides a moral frame through which the reader can evaluate Abu Zayd’s behaviour. Their encounters create a dialectic—between cynicism and idealism, between artifice and truth. This dynamic adds psychological depth to the stories, making them not only entertaining but also reflective and provocative.

Ultimately, Maqamat al-Hariri does not offer clear-cut answers. Instead, it invites us to ponder the ethics of performance, the value of knowledge, and the fine line between survival and deceit. In Abu Zayd, we see the embodiment of human ingenuity—flawed, fascinating, and endlessly resourceful.

Al-Harith – The Witness and the Measure

While Abu Zayd al-Saruji is the dazzling centre of Maqamat al-Hariri, it is the narrator, al-Harith ibn Hammam, who offers the structure, perspective, and moral weight that bind the entire work together. Often overlooked, al-Harith plays a vital role—not merely as a passive observer, but as an interpreter, questioner, and counterpoint to the flamboyant eloquence of Abu Zayd.

Each maqama unfolds through al-Harith’s voice. He introduces the setting, encounters Abu Zayd in disguise, marvels at his performance, and often ends up being tricked or surprised. Yet with every encounter, al-Harith deepens his understanding of Abu Zayd, and by extension, so do we. His reactions are our reactions: admiration, suspicion, amusement, and sometimes disapproval.

Al-Harith is not a blank slate; he has his own voice and personality. He is an educated man, a traveller, someone with an eye for rhetorical beauty, but also a sense of ethics. He serves as a kind of moral compass—gently questioning the values and implications of Abu Zayd’s actions. Through him, the reader is encouraged to reflect: Is verbal brilliance enough, or should it serve a greater good?

The relationship between Abu Zayd and al-Harith is layered with tension and mutual respect. Abu Zayd never addresses al-Harith directly as a friend or follower, yet al-Harith continues to seek him out, listen to him, and report his words in meticulous detail. Over time, a rhythm develops: the encounter, the recognition, the performance, and the vanishing act. Al-Harith becomes a literary device through which repetition is made meaningful, turning each maqama into both a variation and a continuation.

Moreover, al-Harith symbolises the attentive audience—those who seek not just entertainment, but wisdom; not just style, but substance. In a way, he also represents the reader of classical Arabic literature, someone who values linguistic precision, cultural nuance, and ethical reflection. Without al-Harith, the maqamat would lose their anchor; Abu Zayd’s brilliance would float untethered, unexamined.

Thus, in Maqamat al-Hariri, al-Harith ibn Hammam is far more than a literary device. He is the steady hand recording the storm, the mirror reflecting the trickster’s face, the voice that tempers excess with introspection. Through him, the maqamat become not just tales of adventure and eloquence, but meditations on meaning, morality, and the enduring power of language.

The Art of Imitation – Echoes of Tradition in Hariri’s Craft

One of the most fascinating aspects of Maqamat al-Hariri lies in its relationship with the literary heritage of the Arabic language. Hariri’s work is not created in isolation—it draws deeply from, plays with, and pays homage to earlier traditions, most notably that of Badi’ al-Zaman al-Hamadhani, the inventor of the maqama genre. But where al-Hamadhani pioneered, al-Hariri refined and elevated.

Al-Hariri’s maqamat are often seen as the high watermark of classical Arabic prose. His language is richly ornate, filled with complex rhetorical devices, internal rhymes, intricate puns, and stylised rhythms. These features were not merely for show—they were the height of literary artistry in the classical Arabic tradition, and Hariri mastered them with near-unmatched dexterity.

Imitation, in the classical Arab-Islamic world, was not seen as plagiarism, but as a form of literary excellence. It was the deliberate and respectful act of engaging with revered forms and voices from the past. Hariri, in his preface, explicitly acknowledges that he is following in the footsteps of al-Hamadhani, yet he dares to outdo him in breadth, depth, and polish. His fifty maqamat are more structurally balanced, thematically expansive, and stylistically virtuosic than those of his predecessor.

Moreover, Hariri embeds numerous allusions and quotations from the Qur’an, hadith, Arabic poetry, and pre-Islamic lore. His readers—educated members of the literate elite—would have recognised these references and appreciated their placement and transformation. It was a kind of literary game, where recognition led to deeper appreciation. The maqamat thus functioned as a museum of Arabic eloquence, a showcase of what the language could achieve.

At the same time, Hariri’s maqamat are never dry or merely ornamental. The stories pulse with life—filled with humour, irony, social commentary, and moments of emotional poignancy. His work demonstrates that literary form and cultural insight are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, through the play of language, he invites readers to reflect on society, ethics, and human nature.

In this way, Hariri exemplifies the classical principle of taḥmīd wa-taḥmīd—praising the language by performing it. The maqamat are both homage and innovation, tradition and transformation. They remind us that the greatest literature does not sever itself from the past; rather, it listens to its echoes, then adds its own voice to the chorus.

Language as Game, Weapon, and Veil

In the universe of Maqamat al-Hariri, language is never a neutral medium—it is a game to be played, a weapon to be wielded, and at times, a veil that conceals more than it reveals. The entire work is a tribute to the astonishing potential of the Arabic language, and Hariri explores this potential through both form and content, turning each maqama into a masterclass in verbal acrobatics.

At the surface level, Hariri delights in the sheer playfulness of language. Riddles, puns, palindromes, acrostics, and alliterative sequences abound. For readers trained in classical Arabic rhetoric (balagha), this was a source of intellectual delight—a demonstration of linguistic prowess that rewarded close reading. Language becomes an elaborate dance, where meaning and music blend in equal measure.

Yet behind the aesthetic brilliance lies something deeper. Abu Zayd, the trickster orator at the heart of each maqama, uses language not merely to dazzle, but to survive. He persuades, deceives, entertains, and escapes—all through the power of his words. He poses as a preacher, a beggar, a scholar, a mystic—adopting whichever voice best suits his needs. His mastery of language gives him social mobility in a world otherwise rigid with hierarchy.

But this same power makes the reader wary. Is Abu Zayd a hero or a fraud? Is eloquence a virtue in itself, or does it demand a moral purpose? Hariri never resolves this tension; instead, he lets it simmer beneath the surface. Through Abu Zayd, he questions the limits of language. Can truth exist within performance? Can sincerity survive in a world where every word may be a mask?

Moreover, Hariri plays with genre expectations. A maqama might begin as a sermon, turn into satire, and end in poetic lamentation. The audience is kept guessing—not only by the plot, but by the tone and style. This unpredictability mirrors the slipperiness of language itself: ever-shifting, multifaceted, and open to manipulation.

In this literary landscape, words are never just words. They are tools, traps, shields, and spells. Hariri invites his readers to marvel at language’s beauty, but also to remain alert to its dangers. The maqamat, then, are not simply exercises in eloquence. They are philosophical inquiries, cleverly disguised as tales of adventure and wit.

In the world of Hariri, to master language is to hold power—but whether that power illuminates or deceives, liberates or ensnares, remains always in question.

The Enduring Legacy of Hariri and the Maqama Tradition

As we arrive at the final maqama, both within Hariri’s collection and this series, it is only fitting to reflect on the lasting legacy of Maqamat al-Hariri—a text that not only epitomises the art of classical Arabic prose but also continues to resonate across centuries, cultures, and scholarly disciplines.

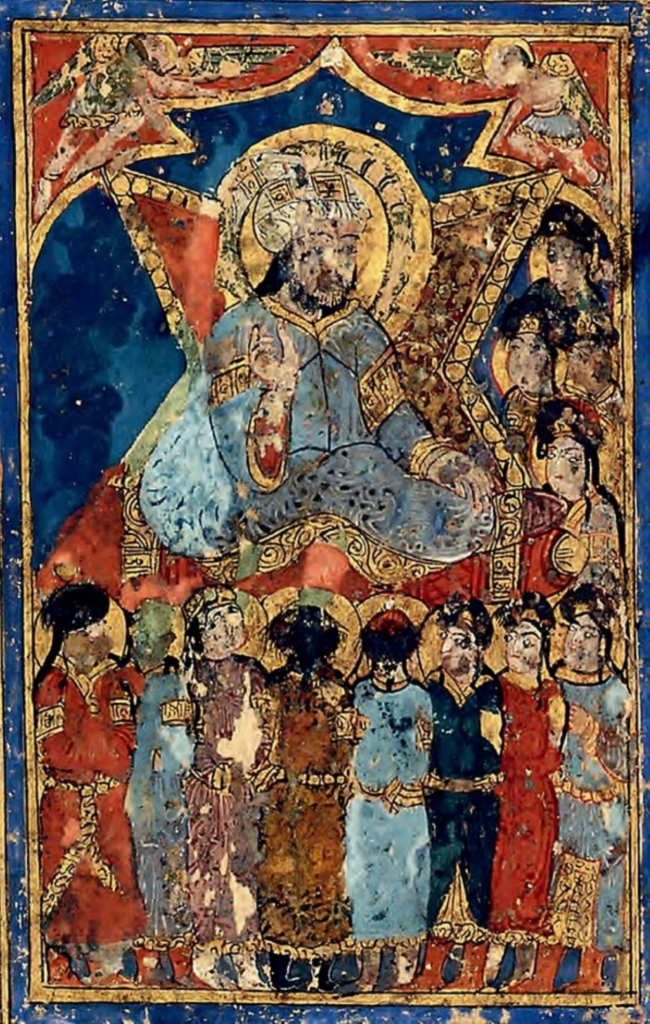

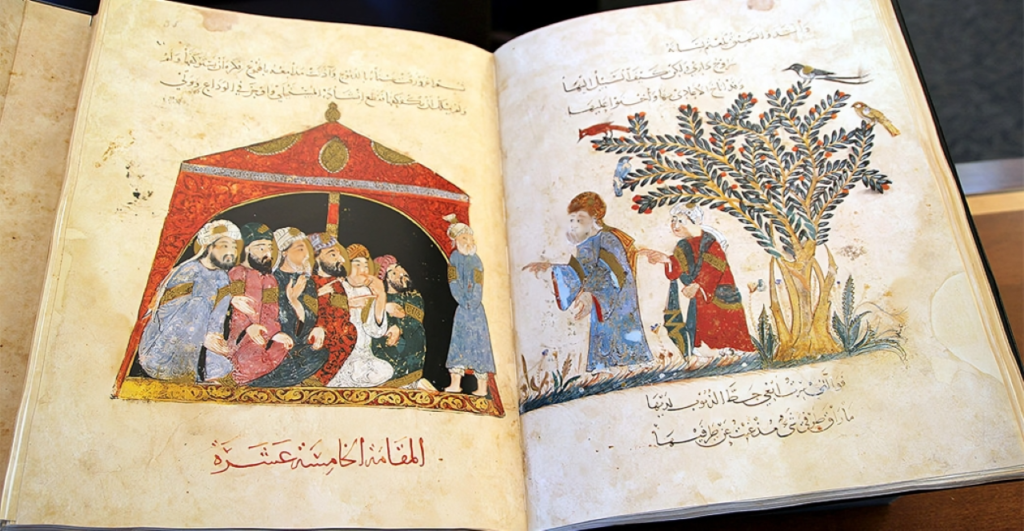

Hariri’s maqamat were not merely admired in his own time; they became a fixture of Arabic literary education. For generations, aspiring writers, poets, and orators studied the Maqamat as a textbook of style and substance. Its popularity led to countless commentaries, manuscript copies, and illustrated versions—most famously the 13th-century Baghdad manuscript, which survives today in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, adorned with exquisite miniatures that visually interpret each maqama.

The character of Abu Zayd al-Saruji, the eloquent rogue at the heart of the stories, became an archetype in Arabic literature—a symbol of the wandering wise man, the trickster-philosopher who outwits the world with nothing but his tongue. Yet Hariri did more than just entertain. Through satire, irony, and theatricality, he held up a mirror to society, exposing its hypocrisies and contradictions.

In the modern era, the Maqamat have intrigued scholars of literature, linguistics, translation, and even performance studies. The richness of the Arabic language, the cultural allusions, and the narrative complexity offer endless material for interpretation. It is a text that defies easy categorisation—at once didactic and humorous, sacred and profane, rooted in tradition yet overflowing with innovation.

One of the most remarkable features of Maqamat al-Hariri is its multilingual afterlife. It has been translated into Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Latin, German, French, and English—each time requiring extraordinary effort to convey its rhetorical beauty and linguistic dexterity. Many translators have admitted that rendering the maqamat into another language is among the greatest challenges in the field of literary translation.

And yet, even when the precise nuances are lost, the Maqamat remain alive. They continue to be read, studied, and performed—whether in classrooms, scholarly circles, or cultural festivals. In Hariri’s vision, the Arabic language was not merely a tool of expression; it was a sacred inheritance, a field of play, and a site of resistance.

Today, Maqamat al-Hariri remind us of literature’s highest calling—not merely to reflect life, but to reshape it through wit, wonder, and wisdom. The stories may be ancient, the language ornate, the settings far removed from our own—but the questions Hariri poses still matter. What is the role of the artist in society? Where does eloquence end and ethics begin? And can truth ever truly be separated from performance?

As readers and inheritors of this dazzling tradition, we are invited not merely to observe—but to respond. The maqama, after all, was always meant to be a dialogue.

The Maqamat al-Hariri – A Literary Monument of Wit, Word, and Wisdom

The Maqamat al-Hariri stands as a towering achievement in Arabic literature, a testament not only to linguistic brilliance but to the cultural, intellectual, and social currents of its time. Across our ten-part exploration, we have seen how this 11th-century masterpiece defies easy categorisation. It is not merely a collection of stories—it is a multilayered performance, a mirror to society, and a monument to the power of language.

At the heart of the maqamat lies a singular figure: Abu Zayd al-Saruji, the travelling trickster whose silver tongue can open doors, inspire crowds, or slip him out of trouble. He is no mere conman; rather, he is a shape-shifter, philosopher, social critic, and at times, a vessel of profound truth. Through his orations and escapades, Hariri invites us to question the boundaries between eloquence and ethics, truth and theatrics.

The world Hariri presents is one where words are the ultimate currency. Whether used to charm a crowd, challenge authority, or survive adversity, language in the maqamat is fluid, strategic, and beautiful. Yet this linguistic mastery is never without ambiguity. Is eloquence a virtue or a vice? Can rhetoric uplift society, or does it serve only to veil deceit? Hariri does not preach; he performs—allowing readers to draw their own conclusions.

Stylistically, the maqamat are a feast. Hariri’s use of rhyme, rhythm, pun, and intricate rhetorical devices displays not only command over Arabic prose, but a desire to stretch the medium to its artistic limits. This is not literature for the passive reader; it demands engagement, attentiveness, and a reverence for the richness of language itself. And in doing so, it rewards the reader with laughter, insight, and wonder.

Culturally and historically, Maqamat al-Hariri emerged during the Abbasid twilight—an era rich in scholarship but rife with social disparity. Hariri captures the contradictions of his age with subtlety and satire. His work draws from classical Arabic heritage while innovating its form, blending prose with poetry, wisdom with farce, piety with parody.

The impact of Hariri’s maqamat cannot be overstated. They were memorised, taught, illustrated, translated, and debated for centuries. From the madrasa to the manuscript workshop, from the mosque courtyard to the royal court, the maqamat lived not only on the page but in performance. Their legacy extends beyond the Arab world, influencing Persian, Turkish, and European literary traditions alike.

Today, the Maqamat al-Hariri remain relevant—not because they speak directly to modern dilemmas, but because they challenge us to think critically about the nature of performance, persuasion, and power. In a world still dominated by speech, spin, and spectacle, Hariri’s tales feel startlingly familiar.

In the end, the maqamat do more than entertain. They ask us what it means to be human in a world shaped by words—words that can liberate or deceive, illuminate or obscure. Hariri’s genius lies not only in crafting exquisite language, but in reminding us that language, like life, is never simple. It is a theatre, and we, the readers, are both audience and actor.

Thus concludes our journey through the maqamat—not with a moral, but with an invitation: to read more deeply, to listen more carefully, and to remain ever aware of the fine line between eloquence and illusion.