Understanding the Shah Bano case is essential for anyone seeking to comprehend the complex relationship between society, religion, and politics in the Indian subcontinent. From a purely legal standpoint, the case was a routine maintenance claim filed under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). Yet, remarkably, this seemingly ordinary litigation went on to alter the trajectory of Indian politics and society in profound ways.

In 1932, Shah Bano married Mohammad Ahmed Khan, a prominent lawyer from Indore. The couple had five children, and for many years their married life proceeded without major disruption. However, at a later stage Ahmed Khan took a second wife. Under the Muslim personal law then prevailing, he was not required to obtain Shah Bano’s consent before doing so.

Although the second marriage deeply affected Shah Bano emotionally, she attempted to adjust to the new circumstances. Within a short period, however, her situation deteriorated significantly. Her status within the household declined, and both she and her children began to face neglect, disrespect, and increasing emotional hardship.

Finally, in 1975—after nearly forty-three years of marriage—Ahmed Khan expelled Shah Bano from the matrimonial home.

At that time, Shah Bano did not immediately approach the courts. Instead, she first sought resolution through relatives and respected elders within the local Muslim community. They appealed to Ahmed Khan either to take her back or, at the very least, to provide financial maintenance. These appeals, however, carried no legal force, and Ahmed Khan refused to comply.

As informal mediation continued for nearly three years, Shah Bano and her children fell into severe financial distress. Their savings and jewellery were gradually exhausted. Her sons, who had only recently begun practising law, earned very little, and maintaining a household of five children became nearly impossible with occasional small jobs and limited help from relatives.

Under these circumstances, Shah Bano was eventually compelled to seek legal remedy. In April 1978, she filed a maintenance claim under Section 125 of the CrPC—a secular provision applicable equally to citizens of all religions.

Shah Bano sought a monthly maintenance payment of 500 rupees. At the time, Ahmed Khan’s monthly income was approximately 5,000 rupees, making the amount requested comparatively modest. Nevertheless, he refused to pay even this sum.

It is important to note that these events unfolded during a period when Pakistan—despite being established as an Islamic state—had already abolished the practice of instant triple talaq and made the consent of the first wife mandatory for a second marriage. At the same time, Hindu women in India enjoyed legally recognised rights to long-term maintenance, calculated on the basis of the husband’s income, the wife’s own property, and the standard of living established during marriage.

The situation of Muslim women in India, however, was markedly different. Under the pretext of separate “religious personal laws,” divorced Muslim women had little effective legal protection. The central legal complication in the Shah Bano case arose from the constitutional protection granted to minority personal laws—an ambiguity that Mohammad Ahmed Khan, himself an experienced lawyer, strategically utilised.

His principal argument was that the Constitution of India granted him special protection in matters governed by religion. Since marriage, he contended, was a religious institution, secular laws could not be applied to compel him to provide maintenance. He maintained that he was bound only by Islamic Sharia law, which, according to his interpretation, imposed no obligation upon a husband to support a divorced wife after the expiry of the iddat period, provided the agreed dower (mehr) had already been paid.

Thus, his central defence was that, under Sharia, he owed Shah Bano nothing beyond the legally prescribed obligations already fulfilled.

As soon as the case was filed, it began attracting nationwide attention. At the time, it was almost unprecedented for a Muslim woman to approach a secular court seeking maintenance in this manner. The courts, too, found themselves in a delicate position due to the constitutional protection afforded to religious personal laws. Yet the humanitarian dimension of the case was so compelling that it could not be ignored.

Shortly after proceedings commenced, several distinguished lawyers voluntarily came forward to assist Shah Bano. Initially, the court itself appeared somewhat hesitant about admitting the case, and many observers feared it might be dismissed outright. Ultimately, however, the matter was formally registered, and regular hearings began.

Once proceedings were underway, Ahmed Khan began pressuring Shah Bano to withdraw the case. When she refused, he pronounced divorce through triple talaq in November 1978—while the case was still pending—and argued in court that, since Shah Bano was no longer his wife, the question of maintenance under Islamic personal law did not arise.

At this point, the central conflict of the case emerged: did hearing such a claim amount to challenging the constitutional protection of religious personal laws?

A significant section of Muslim religious scholars publicly supported Ahmed Khan, arguing that the case represented state interference in the religious freedom of Muslims. They contended that where personal law was explicit, secular courts had no authority to intervene.

In contrast, Shah Bano’s lawyers advanced a fundamentally different argument. They emphasised that Section 125 of the CrPC was a wholly secular provision intended to prevent destitution and vagrancy in society. Regardless of whether a woman was Hindu, Muslim, or Christian, if she was divorced and unable to support herself, the state had a duty to provide minimal legal protection. Personal laws, they argued, could not override such welfare legislation.

They further advanced several specific arguments:

First, Shah Bano had not left the matrimonial home voluntarily; rather, her husband had forcibly expelled her and her children. Under the law, when a husband refuses without just cause to maintain his wife, she is entitled to relief under Section 125 of the CrPC.

Second, it would be profoundly inhumane to abandon a woman—who had spent forty-three years in marriage and was now elderly and unable to work—after providing for her only during the ninety-day iddat period. Even if the marital relationship had formally ended, the former husband’s social and moral responsibility could not be deemed extinguished.

Third, the Shariat Application Act of 1937 primarily governs civil matters, whereas Section 125 of the CrPC is a preventive criminal provision designed to avert destitution. A civil custom or personal law cannot nullify the protections granted by a criminal statute.

Fourth, the dower (mehr) represents a financial entitlement arising at the time of marriage; it cannot be treated as a substitute for lifelong maintenance following divorce.

Fifth, Shah Bano possessed no independent and stable source of income, and given her advanced age it was unrealistic to expect her to earn a livelihood. In contrast, Mohammad Ahmed Khan was a well-established and affluent lawyer in Indore with a monthly income of approximately 5,000 rupees—an amount considered substantial at the time. His refusal to maintain his wife despite clear financial capacity constituted a direct violation of Section 125.

Sixth, at the time the case was initiated the divorce had not yet taken legal effect, and therefore Shah Bano had filed her petition in her capacity as a legally recognised wife. Counsel further emphasised that Section 125 was a social welfare provision applicable to all citizens irrespective of religion, and that the civil magistrate possessed full jurisdiction to pass orders under it regardless of the husband’s personal law.

After hearing all arguments, the Magistrate’s Court in Indore delivered its judgment in August 1979 in favour of Shah Bano. However, the court fixed the monthly maintenance at only 25 rupees.

Given Mohammad Ahmed Khan’s income and social standing, the amount was widely regarded as absurdly inadequate. Shah Bano’s lawyers argued that awarding merely 25 rupees to the wife of a prosperous lawyer was deeply humiliating and wholly insufficient to support her household, particularly as she had five children to maintain.

Consequently, Shah Bano was compelled to approach a higher court. In 1979 she filed a criminal revision petition before the Madhya Pradesh High Court (Criminal Revision No. 320 of 1979). Her case there was undertaken by the distinguished lawyer Danial Latifi.

By this time, the matter had begun to generate intense nationwide debate. A significant section of Muslim religious scholars had publicly sided with Shah Bano’s husband and were delivering speeches and issuing statements across the country opposing the litigation. As a result, the dispute quickly acquired a political dimension. It was no longer merely a private maintenance case; it was gradually transforming into a major confrontation between the authority of the state and the claims of religious personal law.

The Madhya Pradesh High Court accepted the arguments advanced by Shah Bano’s counsel. On 1 July 1980, the court set aside the Magistrate’s order of 25 rupees and enhanced the monthly maintenance to 179.20 rupees. Although still less than the 500 rupees originally sought, the judgment represented a significant legal victory for Shah Bano.

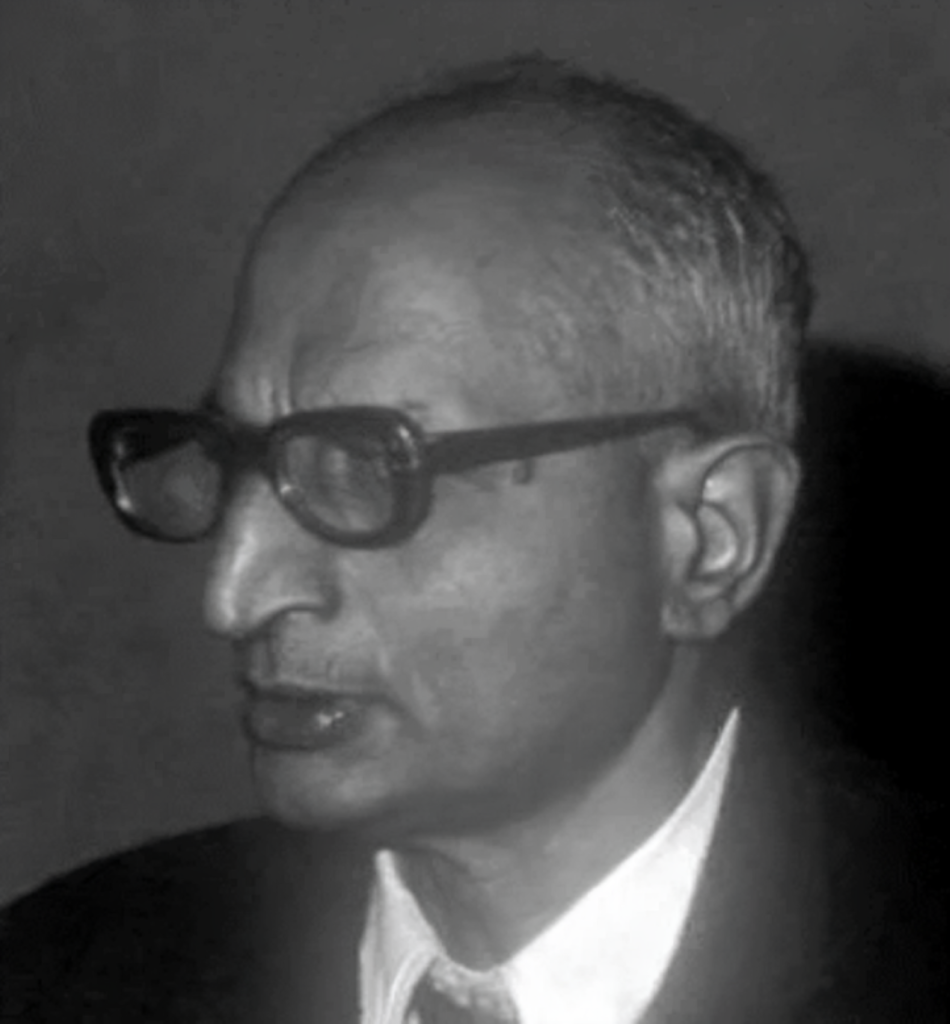

Angered by this decision, Mohammad Ahmed Khan filed an appeal before the Supreme Court of India in 1981. This appeal would eventually culminate, in 1985, in one of the most widely discussed and controversial judgments in the history of Indian law.

Before the Supreme Court, the arguments advanced on behalf of Mohammad Ahmed Khan, as well as those presented by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, were extensive and carefully structured.

Their principal contention concerned the limits imposed by Sharia. According to their interpretation of Islamic law, a husband is obligated to provide maintenance to a divorced wife only during the iddat period—approximately three months—and any payment beyond that would be contrary to Sharia.

They further argued that since the agreed dower had already been paid at the time of marriage and the maintenance due during the iddat period had been fulfilled, Section 125 of the CrPC was not applicable. They cited sub-clause 125(3)(c), asserting that once the amount payable under customary or personal law had been settled, no additional claim for maintenance could be entertained.

Another major argument concerned religious freedom. Invoking Article 25 of the Constitution of India, they maintained that Muslims possessed the constitutional right to follow their own religious personal laws. Any Supreme Court order directing lifelong maintenance under Section 125, they contended, would constitute direct interference in the religious freedom of the Muslim community.

They also advanced a highly controversial claim regarding the nature of divorce. Once a marriage had been dissolved, they argued, the relationship between husband and wife ceased entirely, and the acceptance of money from a former husband after divorce would be religiously impermissible.

In response to these submissions, Shah Bano’s counsel, Danial Latifi, adopted a historic and innovative legal position. He directly cited the Holy Qur’an, quoting verse 241 of Surah Al-Baqarah—“Wa lil-mutallaqati mata‘un bil-ma‘ruf”—which provides that divorced women are entitled to fair and reasonable provision.

Latifi explained that the Qur’anic term mata‘ did not merely signify maintenance for a short, three-month period; rather, it referred to a proper provision sufficient to ensure that a divorced woman could live with dignity. It represented not temporary assistance but a moral and social obligation rooted in Islamic principles themselves.

He argued that, if the Supreme Court were to grant maintenance to Shah Bano, such a decision would not contradict Islam; on the contrary, it would reflect the true spirit of the Qur’an’s teachings.

After hearing the full range of arguments and counter-arguments, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court delivered its historic judgment on 23 April 1985. The Court held that Section 125 of the CrPC was a humanitarian provision intended to protect vulnerable citizens and was equally applicable to individuals of all religions.

Rejecting the arguments presented by Mohammad Ahmed Khan, the Court upheld the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s order directing the payment of maintenance at the rate of 179.20 rupees per month.

However, despite this long legal struggle and the historic victory that followed, Shah Bano ultimately did not receive the benefit of the maintenance awarded to her. After the Supreme Court’s judgment, a significant section of the Muslim community, along with the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, denounced the ruling as direct interference in religious affairs. Large-scale protests soon erupted across the country.

Shah Bano herself came under intense pressure from sections of her community and from influential religious leaders. She was repeatedly told that accepting the Court’s decision would amount to taking a position contrary to Islamic law. Gradually, an atmosphere of social isolation was created around her.

Under this mounting pressure, Shah Bano eventually held a press conference in which she declared that if the Supreme Court’s decision was indeed contrary to her religion, she would reject the award of maintenance. In her public statement she said that, since religious authorities had informed her that the judgment was inconsistent with the Qur’an and Sharia, she would refuse to accept the money. She further added that she feared being held accountable before God in the hereafter if she were to accept it.

Even this announcement did not bring the agitation to an end. On the contrary, many conservative religious leaders continued to present the judgment as an example of state intrusion into religion and intensified their nationwide campaign demanding that the decision be overturned.

Following the Supreme Court’s ruling of 23 April 1985, the government of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi initially welcomed the judgment as a progressive and humane step. During May and June of that year, the young minister Arif Mohammad Khan delivered a long and courageous speech in the Lok Sabha defending the Court’s decision on behalf of the government.

Drawing upon passages from the Qur’an and Hadith, he argued that providing maintenance to a divorced wife was not contrary to Islamic principles; rather, it was consistent with the fundamental Islamic values of justice and compassion. His speech received widespread praise among educated and progressive sections of society.

At the same time, however, the Muslim Personal Law Board and conservative religious leaders continued to escalate the issue. Across the country, campaigns were organised claiming that the government was interfering in the internal religious matters of Muslims and seeking to undermine their distinct religious identity.

Thus, what had begun as a private maintenance dispute gradually transformed into a major political crisis, in which the state, religious institutions, and electoral calculations found themselves standing in direct confrontation.

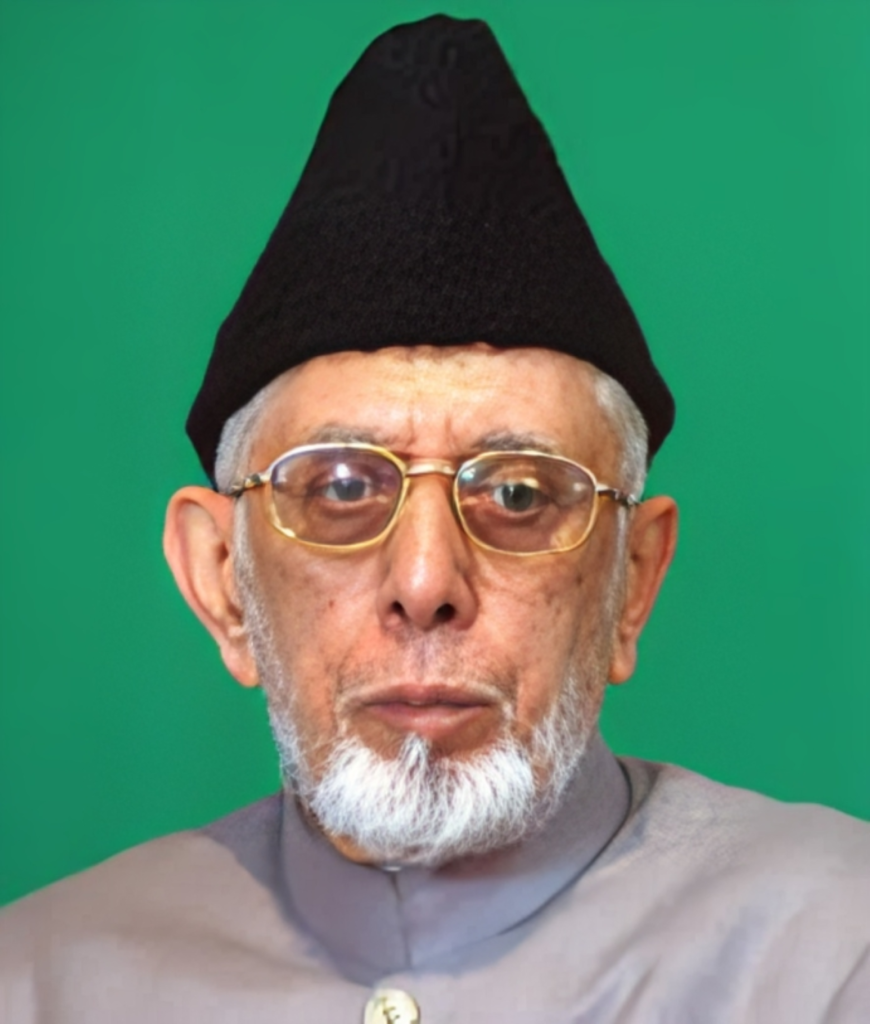

The unprecedented legal and political battle that followed the Shah Bano judgment in the Indian Parliament centred largely on two figures: G. M. Banatwala, a Member of Parliament from the Muslim League, and Arif Mohammad Khan, the young minister in Rajiv Gandhi’s government.

On 10 May 1985, Banatwala introduced a Private Member’s Bill in the Lok Sabha—the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill. He proposed that Sections 125 and 127 of the CrPC be amended to make it explicitly clear that these provisions would not apply to Muslims where they conflicted with Muslim personal law. His central argument was that the Supreme Court had misinterpreted Sharia in the Shah Bano case and that the judgment amounted to a naked interference with the religious freedom of the Muslim community. He even demanded, if necessary, a constitutional amendment to safeguard Muslim personal law.

To oppose this proposal, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi put forward one of the most progressive voices within his government, Arif Mohammad Khan. On 23 August 1985, Khan delivered a speech in the Lok Sabha that is still regarded as one of the finest parliamentary debates in Indian history.

He did not speak merely as a politician but as a scholar of Islamic thought. Quoting directly from the Qur’an and Hadith, he argued that providing maintenance to a divorced wife was not only a humanitarian duty but also clearly supported by Islamic teachings. He described Banatwala’s Bill as both “anti-Islamic” and “anti-women.” It is said that Rajiv Gandhi, deeply impressed by the scholarly nature of the speech, remarked privately that had Arif Mohammad Khan spoken in support of the Bill, he would have dismissed him immediately.

After Khan’s address, it appeared that the government would firmly stand by the Shah Bano judgment. However, in the months that followed, the political situation began to change dramatically.

By December 1985, the political atmosphere had become increasingly uncertain. The Muslim Personal Law Board and conservative religious leaders began exerting intense pressure on Rajiv Gandhi. When the Congress Party suffered heavy losses in several by-elections on 19 December 1985, Gandhi became apprehensive, realising that the fear of losing the Muslim vote bank was not unfounded.

Without informing Arif Mohammad Khan, the top leadership of the government began holding closed-door meetings with conservative religious scholars. Rajiv Gandhi eventually concluded that, in order to retain Muslim electoral support, a political compromise with the clerical leadership had become unavoidable.

Rajiv Gandhi, who had come to power with the largest parliamentary majority in Indian history after Indira Gandhi’s death, was widely regarded as a modern and progressive leader. Many had hoped that his tenure would usher in significant social reforms. Yet, contrary to those expectations, he ultimately chose to side with the conservative clerical establishment.

He decided that a new law would be enacted in Parliament to effectively nullify the Supreme Court’s Shah Bano judgment.

Arif Mohammad Khan felt profoundly betrayed by this sudden reversal of policy. When the government formally announced in February 1986 that it would introduce the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Bill, he resigned from the Council of Ministers in protest. His resignation became a rare example of principled politics, in which a sitting minister stepped down in opposition to his own government’s decision.

Soon afterwards, the government used its overwhelming parliamentary majority to pass the Bill. In history, this episode came to be known as the effective “reversal of the Shah Bano judgment,” as the humanitarian and progressive ruling of the Supreme Court was rendered largely ineffective by a single parliamentary vote.

The political strategy adopted by the Rajiv Gandhi government following the Shah Bano case later came to be described by many analysts as the “politics of appeasement.” Attempting simultaneously to placate conservative Muslim leadership while also balancing Hindu political sentiment, the government’s dual approach ultimately sowed the seeds of long-term instability in Indian politics.

Although the Muslim Personal Law Board welcomed the 1986 legislation, progressive citizens, women’s rights activists, and large sections of Hindu society expressed strong resentment. Hindu religious leaders and political organisations—particularly the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP)—accused the government of undermining both the Constitution and the authority of the Supreme Court for the sake of electoral advantage.

Critics argued that the legislation was not merely a legal amendment; rather, it represented the denial of a vulnerable elderly woman’s rightful claim and the state’s endorsement of medieval religious practices.

In an attempt to manage the growing public discontent and maintain political balance, the Rajiv Gandhi government soon adopted another highly controversial decision: the unlocking of the disputed Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi site in Ayodhya.

Since 1949, the main gates of the Babri Masjid had remained locked, and only a priest was permitted to conduct worship there once a year. Beginning in 1984, the Vishva Hindu Parishad had been demanding that the locks be opened and had launched campaigns, including religious mobilisations and processions, to support the construction of a Ram temple at the site.

On 1 February 1986, at the height of the nationwide debate over the Shah Bano legislation, District Judge K. M. Pandey of Faizabad ordered that the locks be opened, allowing Hindus to offer prayers freely at the site. It is widely believed that the Rajiv Gandhi government’s tacit approval facilitated the swift implementation of the order, which was executed within hours and even broadcast live on the state-run television network, Doordarshan.

This single decision eventually propelled India into a prolonged phase of political and communal conflict, culminating years later in escalating tensions, violence, and ultimately the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

Political analysts have argued that Rajiv Gandhi believed the strategy would satisfy both communities: Muslim conservatives would be appeased through the Shah Bano legislation, while Hindu sentiment would be accommodated through the unlocking of the mosque gates. In reality, however, the consequences proved quite the opposite.

A significant section of the Muslim community felt that one of their rights had effectively been curtailed while a major religious concession had been granted to Hindu groups in return. This resentment led, in 1986 itself, to the formation of the Babri Masjid Action Committee.

At the same time, the Vishva Hindu Parishad and the BJP portrayed the event as a major victory for their movement and intensified their campaign demanding the construction of a full-fledged Ram temple at the site.

Rajiv Gandhi’s divided policy placed India’s secular framework under severe strain. The Shah Bano controversy and the unlocking of the Babri Masjid together accelerated communal polarisation to an unprecedented degree, the ultimate consequence of which was the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

Meanwhile, the central figure of this history-shaping case, Shah Bano, spent the final years of her life in quiet obscurity and severe financial hardship. She passed away in 1987. The struggle she had initiated undeniably altered the course of India’s legal and political history, yet she herself was unable to enjoy any tangible benefit from that victory. In one sense, history remembered her; in another, the state failed to protect her.

Even after Shah Bano’s death, Danial Latifi did not abandon the cause. Instead, he carried forward the legal battle she had begun. In 2001 he filed another important case, Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001), arguing that the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986 deprived Muslim women of their constitutional rights, particularly the right to equality (Article 14) and the right to life and dignity (Article 21).

A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court, while not striking down the legislation itself, interpreted it in a manner that effectively restored the very rights Shah Bano had sought. The Court clarified several key principles:

First, the distinction between the iddat period and lifelong protection. The Court held that although maintenance payments might technically be limited to the iddat period, the law required the husband to make a “fair and reasonable provision” within that period—meaning an arrangement sufficient to secure the woman’s financial future for the rest of her life.

Second, the possibility of a substantial one-time settlement. The Court directed that a Muslim husband must, within the iddat period, transfer such amount of money or property as would enable the divorced woman to live with dignity for the remainder of her life. In effect, the entire financial security of her future was to be ensured within those ninety days.

Third, the revival of the spirit of the Shah Bano judgment. Even while upholding the statute, the Court effectively reinstated the humanitarian philosophy underlying the earlier decision, emphasising that neither society nor the state could remain indifferent if a divorced woman was left destitute.

At the time of the Shah Bano case, Section 125 of the CrPC contained a statutory ceiling of 500 rupees per month. After the judicial interpretation in the Danial Latifi case, that limitation effectively lost its significance, enabling Muslim women to claim substantially larger financial settlements in accordance with the husband’s means. In this sense, the sacrifices made by Shah Bano were not entirely in vain.

The Shah Bano case is today regarded as a watershed moment in India’s political history. Many analysts believe that the developments surrounding this single case and the decisions taken by the Rajiv Gandhi government laid the foundations for the subsequent rise of communal politics in India.

In the 1984 parliamentary elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party had secured only two seats and was politically marginal. The Shah Bano controversy of 1985–86, however, provided the party with a powerful political issue. The BJP began portraying the government’s actions as “minority appeasement,” arguing that the ruling Congress Party had undermined both the Constitution and the authority of the Supreme Court in pursuit of vote-bank politics. Hindu nationalist organisations, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), propagated the claim that Hindus were being reduced to second-class citizens in their own country.

The political consequences were dramatic. In the 1989 elections, the BJP’s parliamentary strength rose from two seats to eighty-five; in 1991 it increased to 120; and in 1996 the party emerged as the single largest group in Parliament with 161 seats. In 2014 Narendra Modi came to power with an outright majority of 282 seats, and in 2019 the BJP returned to office with 303 seats, subsequently enacting legislation banning instant triple talaq.

Thus, the origins of this long political transformation can be traced back, in large measure, to a single maintenance case filed by an elderly woman—an apparently ordinary lawsuit that ultimately reshaped the legal, political, and social trajectory of modern India.

The Shah Bano Case, the Babri Masjid, and the Political Evolution of India: A Timeline

| Year / Date | Key Event | Political and Legal Impact |

| 1932 | Marriage of Shah Bano and Mohammad Ahmed Khan | Foundation of a marriage that lasted forty-three years |

| 1975 | Shah Bano expelled from the matrimonial home | Exposure of the harsh realities within Muslim personal law |

| April 1978 | Shah Bano files a petition under Section 125 CrPC | First major state-level legal struggle by a Muslim woman for maintenance |

| November 1978 | Triple talaq pronounced during the proceedings | Husband attempts to weaken the case through legal strategy |

| 24 August 1979 | Magistrate Court awards 25 rupees maintenance | Symbol of inadequate justice for a destitute woman |

| 1 July 1980 | Madhya Pradesh High Court fixes maintenance at 179.20 rupees | First major instance of a secular court challenging the limits of personal law |

| 1981 | Appeal filed in the Supreme Court | The issue becomes a national controversy |

| 23 April 1985 | Supreme Court delivers judgment | Historic affirmation of secular legal principles |

| May–June 1985 | Speech by Arif Mohammad Khan | Clear articulation of the state–religion conflict |

| August 1985 | Banatwala introduces amendment bill | First parliamentary attempt to shield Muslim personal law |

| December 1985 | Congress losses in by-elections | Rajiv Gandhi’s political shift begins |

| 1 February 1986 | Unlocking of Babri Masjid gates | First official facilitation of the Ram temple movement |

| February 1986 | Resignation of Arif Mohammad Khan | Major example of principled political dissent |

| May 1986 | Passage of the Muslim Women Act | Effective reversal of the Supreme Court judgment |

| 1986 | Formation of Babri Masjid Action Committee | Beginning of organised Muslim political mobilisation |

| 1986–88 | VHP temple movement intensifies | Religion increasingly transformed into a political instrument |

| November 1989 | Temple foundation ceremony (Shilanyas) | State-level recognition of temple demands |

| September 1990 | Advani’s Rath Yatra | Nationwide communal unrest |

| 1991 | General elections | BJP rises to 120 seats |

| 6 December 1992 | Demolition of Babri Masjid | Severe blow to India’s secular framework |

| 1993 | Mumbai riots and bombings | Peak of communal violence |

| 1996 | BJP emerges as largest party | Hindutva enters mainstream politics |

| 2001 | Danial Latifi case | Judicial revival of the spirit of Shah Bano |

| 2002 | Gujarat riots | Intensification of religious politics |

| 2014 | Modi government (282 seats) | Beginning of single-party majoritarian rule |

| 2019 | Modi government (303 seats) | Consolidation of constitutional power |

| 2019 | Triple Talaq legislation enacted | Legislative closure of the Shah Bano controversy |

| 2020 | Construction of Ram Temple begins in Ayodhya |